From the start of Q3/2025, a string of signals from Malaysia shows the authorities have moved from “advice” to “tightening” with respect to anchorage and ship-to-ship (STS) transfers in waters under Malaysian jurisdiction.

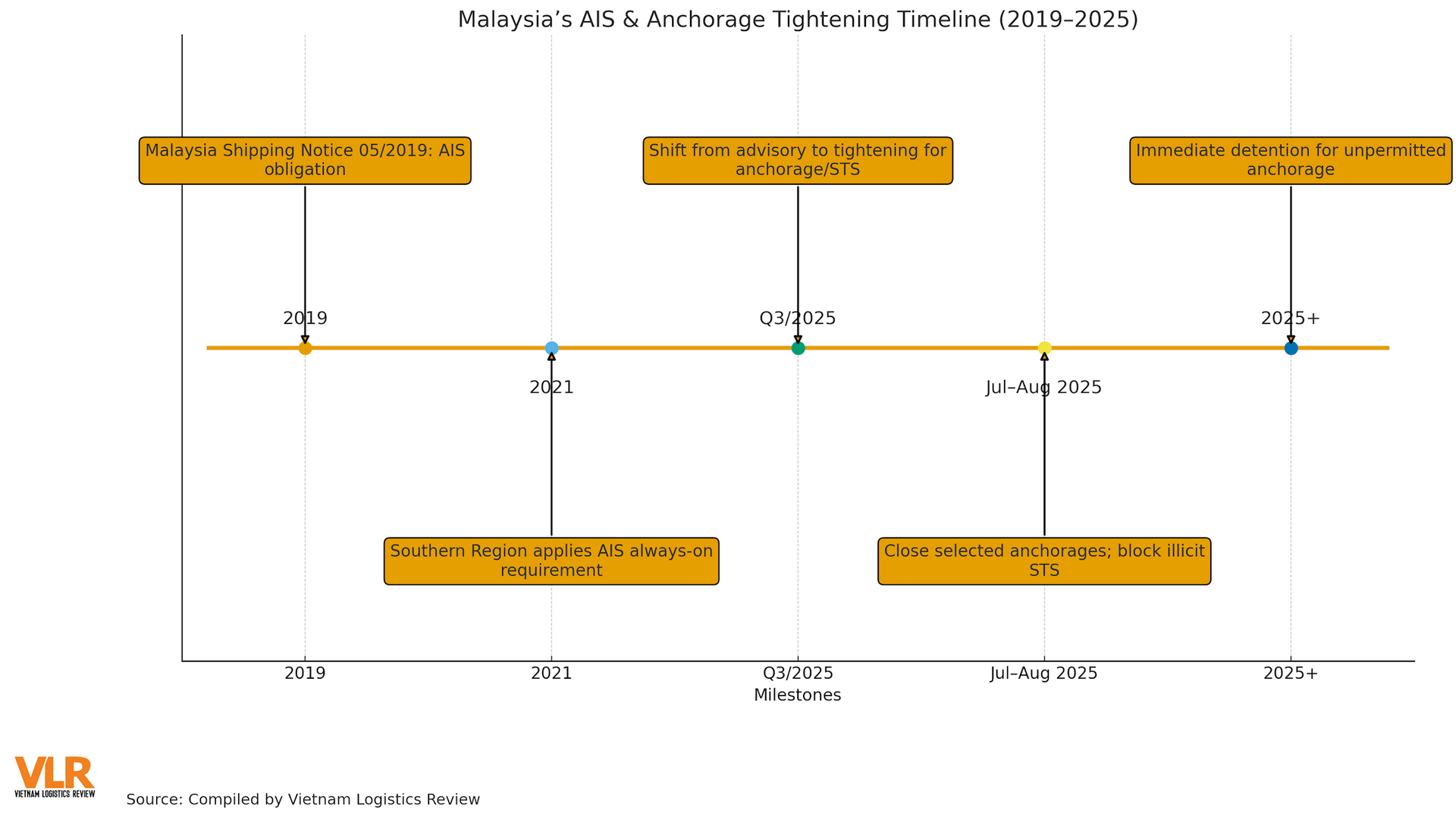

Measures such as requiring AIS to be kept on at all times under recent marine notices, warning of immediate arrest for vessels anchoring without permission, and promising to “close” anchorages that generate illicit STS activity point to a new security-and-compliance strategy at the Malacca Strait gateway.

For Vietnamese businesses that route cargo through the Singapore–Malaysia hubs, this is not merely a paperwork change; it is a test of risk-management capability, data standardization and operational discipline.

From AIS warnings to shutting down “hot” anchorages

Since 2021, the Southern Region Marine Department of Malaysia has implemented and reiterated a rule obliging “authorized vessels” to keep AIS activated at all times when operating in Malaysian waters, based on Malaysia Shipping Notice 05/2019. This requirement follows SOLAS/IMO, but the notable shift is that Malaysia has made AIS an “enforcement condition” governing entry, anchorage and transshipment within its control.

By July–August 2025, the enforcement posture grew more assertive: Malaysia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and enforcement agencies declared they would block illegal STS operations in internal waters and the territorial sea; meanwhile, the trade press recorded notices “closing” certain anchorages to stamp out unpermitted anchoring and opaque oil transfers. The accompanying message is very clear: vessels found anchoring without permission or engaging in unlawful activities will be detained immediately, face substantial fines, and criminal proceedings may be brought against responsible individuals. Recent arrests around Port Klang and eastern Johor serve as concrete warnings to masters, agents and charterers who have grown used to “standing outside” local procedures.

Why is Malaysia “pushing the throttle” now?

The Malacca–Singapore corridor is narrow, crowded and high-risk. Switching off/spoofing AIS, anchoring outside designated areas or conducting STS at “blind” coordinates have helped cargoes of sanctioned origin slip through, creating risks of pollution, accidents and legal exposure for the coastal state. As international sanctions widen their focus from “the ship” to “the service entities” across the chain, Malaysia’s tightening of AIS and anchorage is a way to build an outer legal-and-safety ring while signalling to partners inside and outside the region its commitment to cleaning up maritime activity.

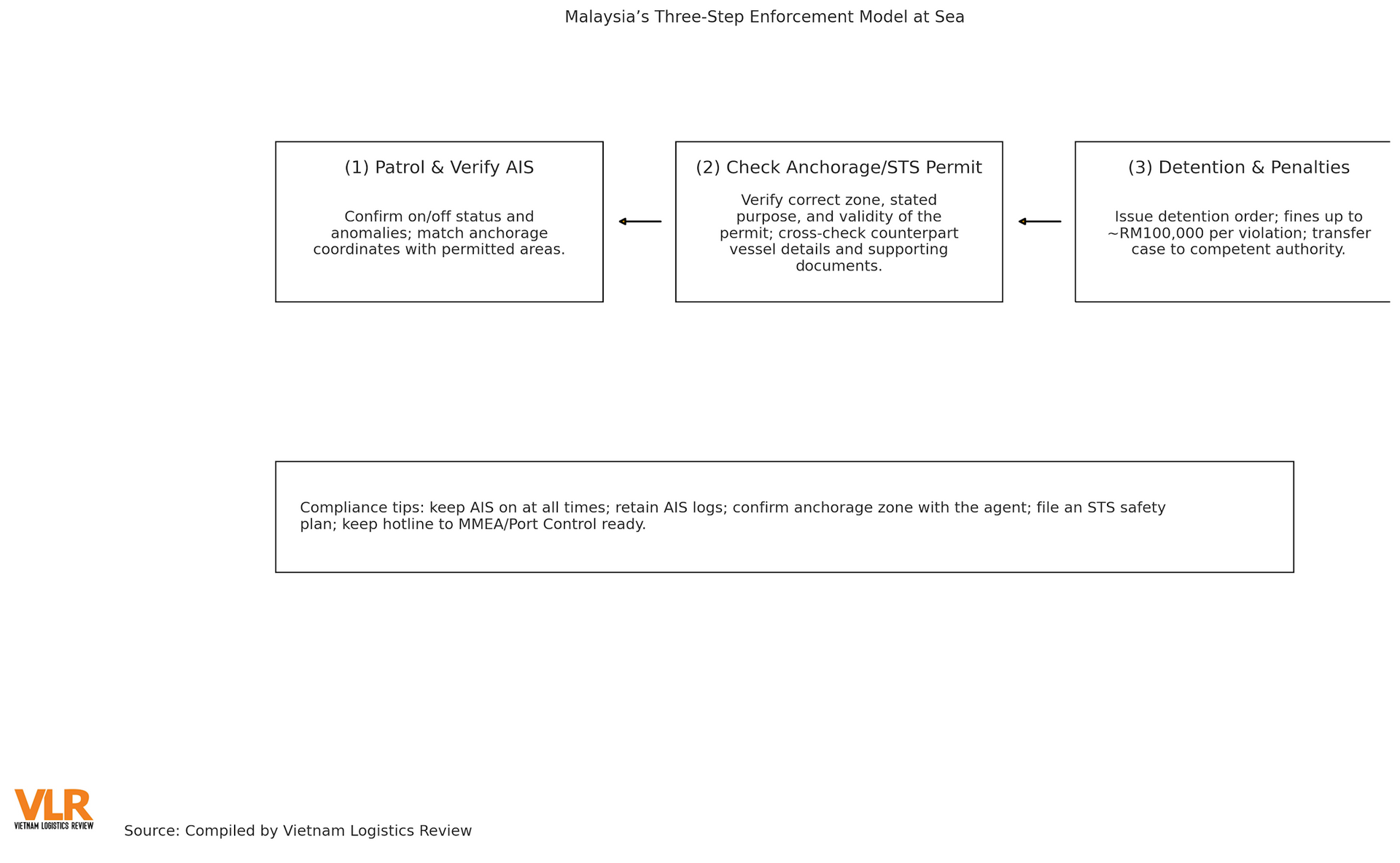

A quick checklist for masters and charterers: do you have an anchorage permit for the specific zone designated by Malaysia’s Marine Department; does the permit clearly state the purpose and validity period; is AIS on continuously with full AIS logs retained; if an STS is planned, has a safety plan been filed to owner/port-authority standards; has the agent confirmed that your anchorage coordinates sit inside the permitted area; have the counterpart vessel’s particulars, insurance and class been cross-checked; are emergency lines to MMEA/Port Control ready. Missing one small link can lead to detention orders, fines and prolonged contractual risk.

The AIS “line”: the traffic light of trust

Under IMO guidance, AIS must operate continuously when a ship is underway or at anchor, unless the master has specific safety-security reasons and even then must record and report fully. In a faster-paced enforcement environment, AIS data is no longer a “nice-to-have” for the operations desk; it has become a compliance gauge. An abnormal off/on cycle, a sudden MMSI/IMO “jump,” or even a small drift beyond the permitted anchorage can trigger deeper scrutiny by authorities and insurers. In other words, AIS is not just a piece of marine equipment; in Malaysia today, it is a signal of how transparent the ship—and the chartering/operating chain behind it—really is.

Where do Vietnamese businesses stand in this new “matrix”?

Vietnamese carriers and owners calling at Port Klang, Tanjung Pelepas or waiting off eastern Johor need to treat the anchorage permit as a “living dossier,” not a box-ticking sheet. Engage the local agent early from choosing the anchorage, checking overlaps between control zones, to confirming weather and hydrographic conditions—to avoid having to “shuffle” the ship in and out of the permitted area. Logistics companies and NVOCCs with a track record of organizing STS for bulk or oil cargoes should self-audit their SOPs: do you cross-check permitted zones by port authority; store and reconcile AIS logs at sufficient resolution; maintain an STS safety standard acceptable to Malaysian regulators; and include contract clauses that clearly allocate responsibility in case of detention.

For cargo owners, risk management lies in balancing time, cost and compliance. “Detour” plans meant to optimize freight or shorten voyages can increase the risk of drifting into zones under heightened inspection. As Malaysia announces closure of certain “sensitive” anchorages, earlier slot bookings, sailing directly to well-controlled hubs, or splitting shipments in line with local permitting capacity will help avoid being “caught outside” the plan.

How enforcement operates on the water

Recent arrests suggest a three-step model: patrol and verify AIS; check the anchorage permit and stated purpose of operations; then apply coercive measures and transfer the case. Fines can reach around 100,000 ringgit per violation, along with the risk of prolonged detention and additional charter-party costs. Notably, some masters were unaware they had entered a permit-required zone due to outdated area limits—an operational error rather than intent, but the legal consequences are not lighter for that. At busy deep-water gateways like Port Klang, procedural delays quickly morph into landside costs for boxes, empty equipment and missed connections to the next sailing.

Regional impact—and lessons for Vietnam

Tighter rules on anchorage/STS in Malaysia are nudging flows toward areas with better permitting and supervision, while shrinking the “playground” of makeshift anchorages where the origin of oil can be disguised. For Vietnam, this policy message points in two directions. First, further standardize and publicize anchorage/STS maps for each port authority, link them to e-permits and real-time AIS alerts. Second, step up data coordination among VTS, port authorities and ship operators to shift monitoring from “after-the-fact” to “pre-check,” minimizing the chance of vessels straying into sensitive zones. The approaches into and out of Cai Mep - Thi Vai and Hai Phong are strong candidates to pilot this framework.

A “light” coordination scheme could include: daily exchange of abnormal AIS alerts among the VTS sides; a catalog of permitted STS coordinates and a fast-track permitting mechanism for direct-service ships; and a three-party hotline when vessels need urgent re-routing/re-anchoring to avoid severe weather. If Vietnamese firms proactively join through associations or major port operators, detention risks will drop sharply while on-schedule reliability will increase exponentially.

Transparency is the cheapest passport

Malaysia is likely to maintain a high enforcement tempo on anchorage/STS and AIS, especially as regional and international media focus on “sensitive” oil flows across the South China Sea. The corridor’s long-term stability depends on all players committing to transparency: masters versed in local waters, local agents decisive on procedures, owners and charterers pledging AIS “lights-on,” and shippers willing to pay a little more in exchange for far lower legal risk. When those conditions line up, the Singapore–Malaysia–Vietnam corridor will become cleaner, safer and more trustworthy for global supply chains.